Dodgy statistics and bad politics: four problems with the Anne-Marie Trevelyan speech on international trade

The unashamedly Thatcherite speech illustrates the contradictions in government policy.

The International Trade Secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan’s latest speech lauded the legacy of Margaret Thatcher from start to finish. She highlighted the 1985 G7 conference in Bonn, which was certainly an important moment in the rise of the economic ideas associated with Thatcher and, in the US, Ronald Reagan. “Thatcher and other G7 leaders”, she said, used the conference to, “usher… in a new era of trade liberalisation and free market capitalism”.

What should we make of this speech? Do we need to simply build on Thatcher’s legacy? Or should we do something else? Here are four big reasons to reject this backward looking and reactionary agenda.

1. The world is moving away from the politics of Thatcher and Reagan

Few people object to trade in general – goods moving from one country to another has, after all, a history stretching back across millennia. But the agenda associated with Thatcher and Reagan wasn’t just about trade. It sought to radically reduce the ability of governments to democratically control their economy and how it relates to the world market. They undermined workers by chasing lower costs in production and building global supply chains based on super exploitation. This agenda saw regulation, like environmental protection and consumer rights, as a bureaucratic barrier to the free market.

The world we live in today was fundamentally shaped by these ideas – sometimes referred to as the ‘Washington Consensus’. But what’s striking about the Trevelyan speech is how at odds it is with current thinking in global economic policy. Recent summits, like the G7 in Cornwall, showed governments appeared to be generally concerned with reducing their reliance on free markets and were re-orientating towards the idea of an interventionist state. As Mariana Mazzucato has argued, if properly pursued this could be a very welcome change:

“Whereas the Washington Consensus minimised the state’s role in the economy and pushed an aggressive, ‘free-market’ agenda of deregulation, privatisation and trade liberalisation, the Cornwall Consensus… would invert these imperatives. By revitalising the state’s economic role, it would allow us to pursue social goals, build international solidarity and reform global governance in the interest of the common good.”

2. If Thatcherism was so good, why does the levelling up agenda exist?

The current government won the 2019 general election through the promise to ‘get Brexit done’ and ‘level up’ the UK. Ironically, this saw the Conservatives win new support in areas of England that had been particularly devastated by the deindustrialisation of the 1980s. The key industries hit hard by Thatcherism, like coal, steel, engineering, ship building, textiles and clothing, were always located in particularly local geographies, and not present everywhere. So, when they were decimated, it built up huge regional inequalities. Many areas would simply never recover.

As Christina Beatty and Steve Fothergill argue, “Manufacturing employment has fallen in just about all parts of the UK but the concentration of industrial job losses north of a line from the Severn estuary to the Wash is especially noticeable. It is the cities, towns and coalfield areas of the Midlands, North, Scotland and Wales that have been hit hardest.”

This raises an obvious problem for the Trevelyan speech. If Thatcherism was so great, then why did it level down Britain, leaving some parts of the country devastated in its wake?

3. Lies, damned lies and statistics

The speech was peppered with various vast sounding numbers. For example, Trevelyan claimed that, “So far we have agreed trade deals with 70 countries plus the EU – trade worth a whopping £766 billion every year.” But including the UK-EU trade deal in this calculation creates a problem for the wider analysis. By no plausible definition could it be an example of ‘free trade’. In fact, it represents the biggest introduction of barriers to the movement of goods and services across borders in modern British history.

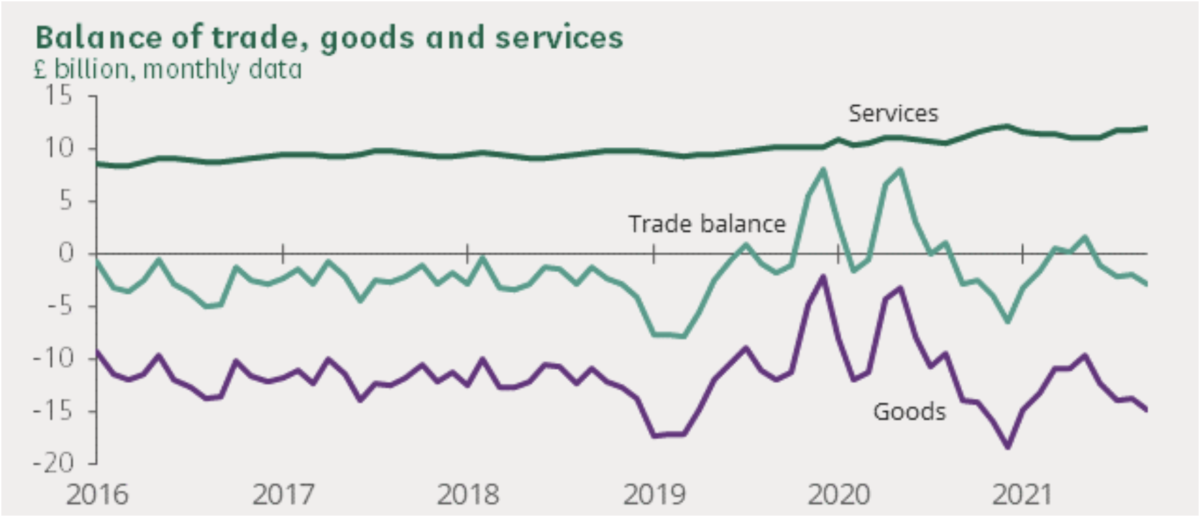

Listening to the speech, you would also be forgiven for thinking the government had been overseeing a vast increase in UK exports. But this is simply not the case. As Graph 1 shows, the UK continues to import more than it exports in goods, while running a trade surplus in services – and despite the ups and downs of Brexit and COVID-19, the trend lines remain pretty static.

The speech also repeated the government’s aim to achieve “exports of a trillion pounds in goods and services per year by 2030”. However, as many have pointed out, the Conservatives had previously set this as a target to be achieved in 2020.

4. A huge hit to GDP from leaving the EU, minimal benefit from new deals

GDP growth is not a good metric with which to measure the economic vitality, let alone sustainability, of a modern economy. But even leaving that aside, the government’s own projections for their new trade deals show only a marginal effect on economic growth. Indeed, Trevelyan claimed in the speech, “We are in negotiations to accede to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, one of the world’s largest free trade areas, composed of 11 Pacific nations with dynamic economies from Chile to Malaysia, Vietnam to Peru. Boasting a combined GDP of more than £8 trillion in 2020.” Yet, she didn’t point out that the government’s own analysis of this deal shows a positive impact on UK GDP of just 0.08% – less than one fortieth of the projected negative hit to GDP from leaving the EU.

What’s more, focusing on GDP can also be misleading. Just because a trade deal has a small impact on overall GDP, doesn’t mean its cost-free. For example, the UK steel sector comes to just 0.1% of UK economic output, 1.2% of manufacturing output, and employs 33,400 people. In short, it is very small. But few argue that having a steel sector is unnecessary and any trade deal that removes its protections would be hugely damaging to the UK.

A similar story exists in food. The Australia trade deal would open up the UK sector to industrially produced food products with lower environmental standards. This means cheap produce in the UK market, undercutting local producers and increasing ‘food miles’ in direct contradiction to the government’s stated agenda on climate change. So, even though agricultural production is only 0.6% of UK GDP, this would have serious negative impacts on farmers and consumers.

***

These contradictions – pro-state, but pro-market, pro-UK industry, but pro-free trade, etc. – are all a sign of the government’s identity crisis. They have won support from many leftist voters in deindustrialised parts of England but remain resistant to many of the policy proposals that could make a real difference to regional inequality.

November 23, 2021

Brexit Spotlight is run by Another Europe Is Possible. You can support this work by joining us today. The website is a resource to encourage debate and discussion. Published opinions do not necessarily represent those of Another Europe.